From Tragedy to Transcendence: Django’s Unlikely Rise

Born Jean Reinhardt on January 23, 1910, in the Belgian village of Liberchies, Django was raised in a Romani caravan. His nickname, meaning “I awake,” would prove prophetic. His early life was marked by poverty, cultural marginalization, and precocious musical talent. By the time he was a teenager, Django was already an accomplished banjo player, performing in dance halls around Paris.

But at age 18, catastrophe struck. A fire swept through his caravan, igniting a pile of celluloid flowers. Django sustained third-degree burns to his left hand and leg. Doctors recommended amputation; Django refused. After a long, painful recovery, he was left with only partial use of his third and fourth fingers on his fretting hand.

Most would have given up the guitar. Django reinvented it.

The Birth of Jazz Manouche

In 1934, Django’s musical destiny changed course when he met violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Together they formed the Quintette du Hot Club de France, one of the first major jazz groups composed entirely of string instruments. In a jazz world dominated by big bands and horn sections, this was revolutionary. Django’s guitar was no longer a background rhythm instrument—it became the solo voice.

Django’s style fused American jazz with the melodies and rhythms of his Romani heritage. He called it “le jazz manouche,” now known internationally as Gypsy Jazz—a genre characterized by fast tempos, minor keys, intricate picking, and expressive vibrato.

Unlike his American contemporaries, Django was largely self-taught. He learned by ear from Louis Armstrong records, and soon developed a technique so singular that even today, it’s nearly impossible to replicate without mimicking his physical limitations.

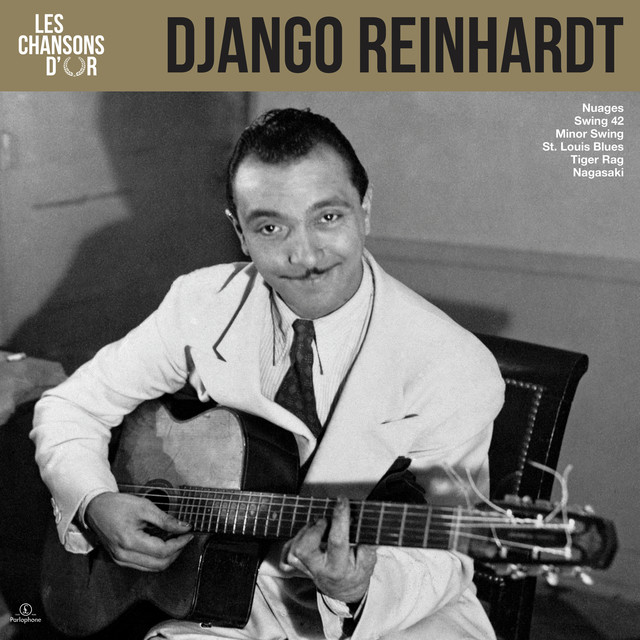

Defining the Sound: Iconic Recordings

Some of Django’s most influential works remain essential listening for any guitarist:

- “Minor Swing” (1937): Co-written with Grappelli, this defining track encapsulates the rhythmic drive and melodic flair of Gypsy Jazz. It has become the gold standard of the genre.

- “Nuages” (1940): A haunting ballad composed during the Nazi occupation of Paris, it served as an anthem of hope and resistance. “Nuages” reveals Django’s depth, tenderness, and poetic phrasing.

- “Djangology” (1935): A joyful, exuberant piece that showcases the playful conversation between Reinhardt’s guitar and Grappelli’s violin.

- “Swing 42” and “Belleville”: Testament to Django’s flair for bebop-like speed years before the style formally emerged.

These tracks are more than musical milestones—they’re cultural artifacts of innovation.

Technique Born of Necessity

Django’s limited left-hand mobility led to astonishing adaptations. He used his index and middle fingers for solos, reserving the two injured digits for chord voicings and occasional support. His arpeggios were often played with dazzling speed and clarity, thanks to his rest-stroke picking technique—a method borrowed from classical and flamenco traditions.

He primarily used Selmer-Maccaferri guitars, known for their distinct D-shaped or oval soundholes and loud, percussive tone. These guitars, with their resonant projection, were ideal for unamplified performances in busy cafés and clubs.

Django’s right-hand technique was equally groundbreaking: precise, aggressive, and expressive. He could create a whisper or a roar with the same stroke, making every note feel intentional and alive.

Playing Under Occupation

When WWII broke out, Grappelli stayed in London while Django returned to France. Despite the Nazi ban on jazz and the persecution of Romani people, Django continued to perform in occupied Paris. He even composed a jazz mass, “Messe des Saintes Maries”, blending liturgical themes with Romani music.

Protected by influential fans and collaborators, Django miraculously survived the war. Afterward, he toured with Duke Ellington in the U.S. in 1946, but the trip was not a success. Django clashed with the structured format of American big band shows and struggled with the absence of his Selmer guitar and familiar rhythm section.

Even so, his playing left a mark. Jazz giants like Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery, and later Pat Metheny and Bireli Lagrène have all cited Django as a vital influence.

The Final Years and Sudden End

By the early 1950s, Django had transitioned to playing electric archtop guitars, embracing the changing jazz landscape. His late recordings reflect a more modern, bebop-influenced style, hinting at a new chapter in his artistry.

But that chapter would never fully unfold. On May 16, 1953, Django Reinhardt died of a sudden stroke at the age of just 43. His funeral in Samois-sur-Seine was attended by thousands, a rare honor for a Romani man in postwar France.

Django’s Enduring Legacy

More than 70 years after his death, Django Reinhardt’s music continues to ignite audiences around the world. His life is a lesson in resilience, innovation, and the boundless power of human creativity. Each June, the Festival Django Reinhardt in Samois celebrates his legacy, drawing players from all over the globe.

Gypsy Jazz has become a global movement. Django’s techniques are studied at conservatories, jammed in parks, and passed down orally among Romani musicians as a living tradition. He didn’t just create a new guitar style—he gave a voice to an entire cultural identity through music.

10 Things You Didn’t Know About Django Reinhardt

- He never learned to read music but could memorize complex compositions after a single listen.

- He recorded with Louis Armstrong, one of his biggest inspirations, though the session tapes are lost.

- He loved painting and often spoke about pursuing it professionally.

- He walked away from his U.S. tour with Ellington mid-way, frustrated by the rigid schedule and formality.

- He composed a jazz Mass for the Romani pilgrimage at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

- He was a sharp dresser, often seen in suits and ties even when busking.

- He once disappeared for months, living in a monastery, playing guitar to the birds.

- He was nearly arrested by the Gestapo, but a German officer recognized and protected him.

- His son Babik Reinhardt became a respected jazz guitarist in his own right.

- He’s cited in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of the earliest guitar heroes influencing rock.

Conclusion: The Genius With Two Good Fingers

Django Reinhardt didn’t just defy the odds—he redefined them. In a world that told him he couldn’t, he played louder, faster, and more soulfully than anyone had before. With two working fingers and an infinite imagination, he created an entirely new musical language.

For anyone who picks up a guitar and dares to do it differently, Django remains a guiding star.

Leave a comment